The new observations revealed surprising connections between the inner corona, with its complex magnetic structure, and the outer corona, where the solar wind flows into the heliosphere, the vast bubble of space surrounding the Sun. “It connects to the stuff that connects to us: the middle corona is where that happens, and we haven’t observed it before,” Seaton said. The middle corona is the place on the Sun that drives the solar wind and big solar eruptions that travel to Earth and can affect various technologies here, including blocking radio communications, damaging power grids and diminishing navigation system accuracy. With this innovative technique, the researchers were able to image a region of the corona that, while important, had been difficult to see.

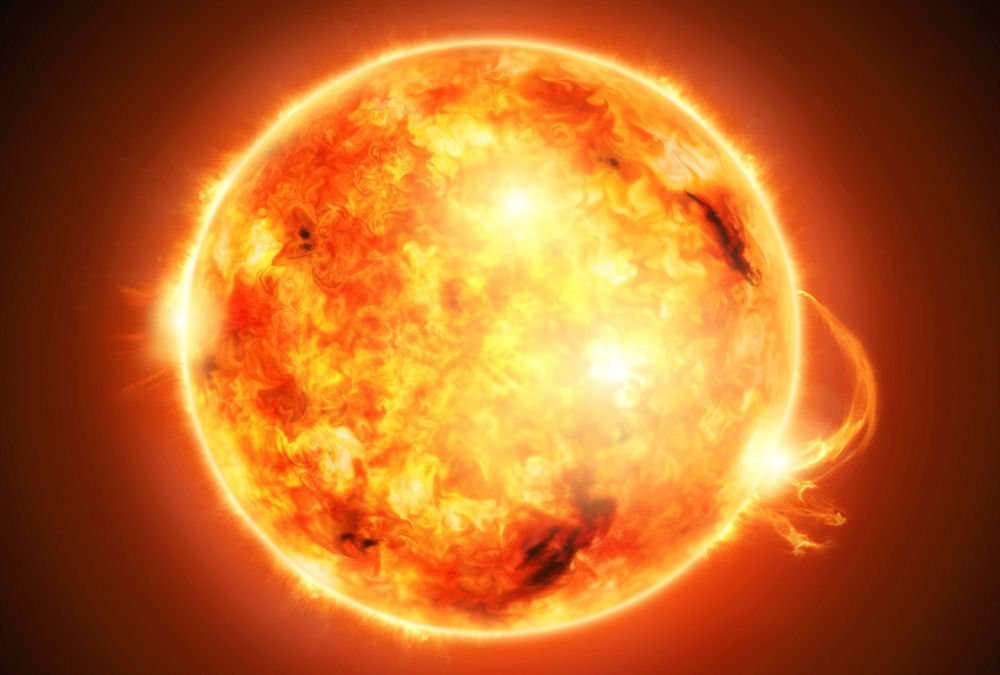

“It didn’t take building a new instrument, but using the instrument in a new way.” “We tiled the images together,” Seaton said. In August and September of 2018, the researchers captured the middle corona by using SUVI to take pictures from one side of the Sun, pointing directly at the Sun, and then from the other side. The study, with co-authors from NASA, the Southwest Research Institute and Lockheed-Martin, was published today in Nature Astronomy. “We were able to create a larger field of view and construct mosaic images of the Sun showing the solar corona in extreme ultraviolet light, to answer questions about how the Sun’s outer atmosphere connects to the surface of the star." “Our instruments focus on the Sun, but not at the heights needed to see these events,” said Dan Seaton, a CIRES scientist in NCEI who led the study. Their observations, from the Solar Ultraviolet Imager (SUVI) on the NOAA GOES-17 satellite, reveal how the middle corona influences the solar wind and eruptions from the Sun, a finding that could improve space weather forecasting. Using a NOAA telescope in a novel way, CIRES researchers working in NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information captured the first-ever images of dynamics in the Sun’s elusive middle corona.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)